‘Hell is neither so certain nor as hot as it used to be’ Bertrand Russell

In Sam Raimi’s movie Drag me to Hell a sweet mortgage adviser Christine Brown succumbs to temptation. To gain a promotion to assistant manager she refuses to give a vulnerable old gypsy woman an extension on her mortgage repayments. Homeless, shamed (and forced to act as a ghastly stereotype) the old woman swears revenge. She physically assaults Christine, smashes up her car, and steals a button from her cardigan. Which is unfortunate for poor Christine as a cursed button places you in the power of the dreaded Lamia.

In Sam Raimi’s movie Drag me to Hell a sweet mortgage adviser Christine Brown succumbs to temptation. To gain a promotion to assistant manager she refuses to give a vulnerable old gypsy woman an extension on her mortgage repayments. Homeless, shamed (and forced to act as a ghastly stereotype) the old woman swears revenge. She physically assaults Christine, smashes up her car, and steals a button from her cardigan. Which is unfortunate for poor Christine as a cursed button places you in the power of the dreaded Lamia.

The Lamia has fallen on hard times, it seems. No longer able to find work in Greek mythology or Keats’ poetry, the poor devil now has to star in unpleasant B-movie features, tormenting bank tellers for three days before dragging them to hell for all eternity. Which, to cut a long story short, the Lamia does to Ms Brown in a flurry of special effects and hammed up acting. (Leaving audiences with a perplexing question…how will Gyspy witches react to the collapse in the housing market?)

Of course this is all meant to be hokum – enjoyable fun. Test audiences in America actually applauded as Christine Brown disappeared into the abyss. With the collapse of the sub-prime market in America, people cheered up at the thought of loan officers in eternal torment. But this wasn’t a sadistic revenge fantasy. Audiences could no more believe that our souls are threatened by demonic powers than they could believe that we are being stalked by bogey men.

Once Luca Signorelli could terrify the faithful with his vision of demons feasting on The Damned Cast into Hell in the Orvieto Cathedral. But we are no longer under the tyranny of mythology. Fear of damnation has been replaced by rather more mundane concerns about finances and relationships. Thus our concerns about eternal punishment are consigned to the pit.

Once Luca Signorelli could terrify the faithful with his vision of demons feasting on The Damned Cast into Hell in the Orvieto Cathedral. But we are no longer under the tyranny of mythology. Fear of damnation has been replaced by rather more mundane concerns about finances and relationships. Thus our concerns about eternal punishment are consigned to the pit.

The Hell that most people don’t believe in isn’t the Hell that Jesus did believe in. The Hell that strains all credulity, a vast mediaeval torture chamber staffed by hungry demons, never appears in the New Testament. Sadistic pictures of Hell were available to Jesus. The book of Judith refers to God putting worms and fire in the flesh of the damned to increase their pain. But when Jesus refers to the worm that does not die and the never ending flame he is talking about Gehenna, the Valley of Hinnom. The people of God could not go there as it was a ceremonially unclean place where idolaters used to sacrifice to strange gods. So being shut out of God’s people is one prominent image for eternal punishment. The other is being shut outside a great feast. Eternal Punishment is a matter of eternal loss and eternal ruin. Eternal torture, by demons or the like, never gets a mention.

Is there any reason to take Jesus’ conception of Hell seriously? Why wouldn’t a good God simply accept and forgive all his creatures? Wouldn’t a good God have provided eternal bliss for us all? Well that’s a nice picture, and one well suited to Hollywood fantasies. But the real world isn’t like that. God can’t have a relationship with us all by Himself. If we freely, under no compulsion, refuse to enter into a proper relationship with God then we can’t expect God to force a relationship onto us.

And we have very good reasons not to seek a relationship with God. Loving God for who He is would mean accepting Him as He is. Accepting God as who He is means accepting that He owns you – every last part of you. There is not one moment of your entire existence that God cannot claim as His own to rule. So if you want to love God you have to surrender your freedom to him completely, and take only what he gives back to you.

It takes two for forgiveness. One to give it, the other to accept it. And accepting forgiveness means that we need to accept that we need to be forgiven. That’s a lot to ask of ourselves, especially when we consider what Christianity teaches was necessary for our forgiveness, the death of God’s Son. Do we really want to believe that we are that bad?

Quite naturally, we don’t want to lose our freedom or our self-respect. But if Hell isn’t a Mediaeval torture chamber neither is Heaven a Disney theme park. Heaven is (at the very least) fellowship with God. But if we don’t want to have God in His rightful place here and now, then we will not want him to rule our lives for all eternity. Christopher Hitchens described the idea of Heaven as a kind of Spiritual North Korea, and he wanted nothing to do with it. He neatly articulated why so many refuse the chance of heaven; many humans value their own autonomy above every other good. Unfortunately these include the goods of eternal love and fellowship with God.

If we opt out of Heaven, and life goes on past the physical grave, then all you have left is Hell. You’ve missed your chance of fulfilment forever. All that is left is eternal ruin. What will the experience of that be like? Scripture does not say. It doesn’t sound as bad as Signorelli’s Damnation. But there is scant comfort in that. Hell is what we get when we refuse God. They say the path to Hell is paved with good intentions. Nonsense. It’s paved with our intention to remain free. And God’s most terrible punishments can be carried out when he gives people exactly what they cherish most.

As it happens, the design argument that Paley offered initially did consider the possibility that we would find some ‘watch-making mechanism’ in nature. But what would explain the ‘watch making mechanism’? We could find an infinitely long series of mechanisms, each making the next mechanism in the series. But sooner or later, Paley reasoned, you would find a Designer, or all those mechanisms making other mechanisms would be inexplicable. Paley couldn’t think of a mechanism that could create other new mechanisms with novel and useful features. Darwin could and so Paley’s science went into the dustbin of history. But one of his design arguments remains unanswered.

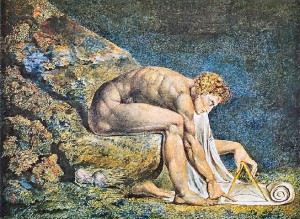

As it happens, the design argument that Paley offered initially did consider the possibility that we would find some ‘watch-making mechanism’ in nature. But what would explain the ‘watch making mechanism’? We could find an infinitely long series of mechanisms, each making the next mechanism in the series. But sooner or later, Paley reasoned, you would find a Designer, or all those mechanisms making other mechanisms would be inexplicable. Paley couldn’t think of a mechanism that could create other new mechanisms with novel and useful features. Darwin could and so Paley’s science went into the dustbin of history. But one of his design arguments remains unanswered. God is unlimited, personal power. We all know what it is to be personal: to be thinking, conscious beings. We can all readily experience personal power – this is simply the power to make choices. Our power is quite limited in nature, as we are finite physical beings. As sole creator, God’s power and awareness could not be limited by anything else. So, because God would be aware of everything that he could do, and everything that he has done, God would know every truth. This idea of God is perfectly meaningful; and if science has taught us anything it is that we should not dismiss an idea because it seems strange or difficult to imagine.

God is unlimited, personal power. We all know what it is to be personal: to be thinking, conscious beings. We can all readily experience personal power – this is simply the power to make choices. Our power is quite limited in nature, as we are finite physical beings. As sole creator, God’s power and awareness could not be limited by anything else. So, because God would be aware of everything that he could do, and everything that he has done, God would know every truth. This idea of God is perfectly meaningful; and if science has taught us anything it is that we should not dismiss an idea because it seems strange or difficult to imagine.