In part one we examined a fairly popular Daily Wire YouTube video in which Sam Harris lamented that the Bible does not condemn slavery.

Ben Shapiro responds that Harris’s has a simplistic view of how religious texts effect social change; Shapiro is quite correct. In fact, it is very easy to see why many Quakers, pietists and evangelicals came to oppose the transatlantic slave trade. They were simply applying the Bible’s condemnation of brutality, greed and racism. It is certainly true that the Bible does not demand the end of slavery. Old Testament laws regulated slavery and the New Testament epistles gave advice to household slaves and their masters. But the slavery condoned by the Old Testament law was of a very different kind than the slavery the abolitionists confronted.

Nor were the abolitionists radically rejecting the traditional teaching of the Church. We need to keep in mind that the church had undermined slavery in Europe, only to see a new kind of slavery created by early modernity. It was this barbaric, dehumanising, industrialised slavery that the abolitionists so passionately and eloquently opposed.

Nor were the abolitionists radically rejecting the traditional teaching of the Church. We need to keep in mind that the church had undermined slavery in Europe, only to see a new kind of slavery created by early modernity. It was this barbaric, dehumanising, industrialised slavery that the abolitionists so passionately and eloquently opposed.

The classical philosophical tradition, from Plato and Aristotle onwards, was quite relaxed about the institution of slavery, assuming that some people were born to be owned by others. But the Christian theology never viewed slavery as desirable or even natural. Most followed Augustine, who could not imagine a world without slavery but who also believed that slavery was an unnatural consequence of human wickedness. Slavery was not part of God’s original design for humanity and was, at best, a necessary evil to be tolerated until the New Heavens and the New Earth. Gregory of Nyssa went further, and produced what David Brion Davis calls “the only surviving all-out attack in antiquity on the enslavement of human beings”.

In Europe the Church generally believed that because the Israelites had not been allowed to enslave one another, Christians should not be allowed to enslave one another either. Furthermore, the belief that one God ruled the nations, and that these nations were all ‘of one blood’, prevented any one racial group from successfully arguing that it had a natural right to enslave another. Gradually, slavery was dying out in Europe; but it was revived by the discovery of the New World. Even then, in response to appeals from Franciscans and Dominicans, Fernando and Isabel of Spain forbade the enslavement of their subjects in 1500. In 1686 Italian Capuchin Franciscan missionaries were able to persuade the Roman Inquisition to pronounce a general condemnation of the slave trade. So opposition to slavery was hardly unheard of before Wilberforce and his comrades.

Far from presenting a problem for the abolitionists, the Torah had a profound influence on their opposition to slavery. According to the books of the law, an Israelite slave, or a slave taken from one of the ethnic groups sojourning in the Promised land, had to be offered freedom after six-years of slavery. Furthermore, an Israelite could only enter slavery voluntarily. Foreign slaves could be purchased from foreign slave traders. However, anyone who kidnapped persons to enslave them faced the death penalty. A master who deliberately killed a slave was to be executed and a slave who had been permanently injured by their master was to be set free.

So the Old Testament did not permit many of the practices essential to the transatlantic slave trade. Moreover, Quaker, Pietist and Evangelical missionaries did not view African slaves as members of a hostile, pagan people but as a mission field. If Jesus died for each individual slave then every slave was a potential convert to Christianity. If it was wrong for Christians to enslave one another then how could it be right to enslave someone who might come to Christ?

So the Old Testament did not permit many of the practices essential to the transatlantic slave trade. Moreover, Quaker, Pietist and Evangelical missionaries did not view African slaves as members of a hostile, pagan people but as a mission field. If Jesus died for each individual slave then every slave was a potential convert to Christianity. If it was wrong for Christians to enslave one another then how could it be right to enslave someone who might come to Christ?

So when George Fox, the founder of the Quaker movement, visited Barbados in 1671, he called on Quakers not only to preach the gospel to slaves but to work for for their eventual emancipation (though he did not call for the abolition of slavery itself). America’s first antislavery tract, The Selling of Joseph, would be penned by the Puritan Samuel Sewall in 1700. The violent and dehumanising treatment of African slaves, and the manner of their acquisition, was denounced even by slave-owning evangelicals like Jonathan Edwards and George Whitefield. And as slaves like Olaudah Equiano and Phillis Wheatley converted to and embraced Christianity it became increasingly difficult to treat Africans as lesser humans.

James Walvin notes that slave owners in English colonies resisted the evangelism of slaves. Missionaries objected to the brutality of slavery, spoke out against the most cruel punishments and gave slaves a voice by listening to their concerns. Moreover, they humanised the slave population by treating them as prospective brothers in Christ. In Barbados slave-holders refused to have their slaves baptised. Neighbouring Catholic islands had no similar objection because the Catholic Church required little of slaves before baptism. Pietistic Protestants demanded their converts receive detailed instruction in the faith. Not only were slaves brought into the Church and humanised by thee missionaries- these Protestants were also demanding that slaves be educated!

James Walvin notes that slave owners in English colonies resisted the evangelism of slaves. Missionaries objected to the brutality of slavery, spoke out against the most cruel punishments and gave slaves a voice by listening to their concerns. Moreover, they humanised the slave population by treating them as prospective brothers in Christ. In Barbados slave-holders refused to have their slaves baptised. Neighbouring Catholic islands had no similar objection because the Catholic Church required little of slaves before baptism. Pietistic Protestants demanded their converts receive detailed instruction in the faith. Not only were slaves brought into the Church and humanised by thee missionaries- these Protestants were also demanding that slaves be educated!

Over time, many Quakers and evangelicals intensified their objections to the slave trade. Edwards son, Jonathan Edwards Jr., and Whitefield’s successor as the pre-eminent evangelist of the age, John Wesley, would both aggressively campaign for the abolition of slavery. In general, their case against slavery was based on the brotherhood of man, Jesus’s command to love neighbour and enemy alike, the Golden Rule, and God’s actions to free the children of Israel from slavery in Egypt. They knew that Paul did not attempt to abolish slavery – but he was in no more a position to campaign for emancipation than he was to overthrow Rome’s pagan rulers. The Old Testament might have permitted slavery, but it nothing in the Bible commanded some humans to make slaves of others and Old and New Testaments praised liberty and forbade cruelty.

The European Christian tradition frowned on Christians enslaving other Christians; evangelicals and their fellow travellers merely went a little further by forbidding Christians from enslaving anyone for whom Jesus died. Evangelical theology respected the individual by insisting that each individual person needed to come to a personal understanding of, and trust in, Christ’s work. The logic of evangelism meant that every person of every ethnicity was potentially a Christian. So slave fields became mission fields and mission fields became churches teeming with brothers and sisters in Christ.

So the evangelicals’ objection to slavery was shaped and strengthened by their biblical and theological commitments – but this was no mere “text-based” morality. Wesley’s tract “Thoughts on Slavery” makes a strong case from both human sympathy and natural law. He strenuously argues for the common humanity of the Africans who were kidnapped to be sold as slaves and against the extreme cruelty inflicted upon them by slave holders. Any system of law which could allow kidnapping for profit, torture for trivial offences, and which executed slaves for pursuing their own freedom, undermined all justice and mercy.

Where is the justice of inflicting the severest evils, on those who have done us no wrong? Of depriving those that never injured us in word or deed, of every comfort of life? Of tearing them from their native country, and depriving them of liberty itself? To which an Angolan has the same natural right as an Englishman and on which he sets as high a value? Yea where is the justice of taking away the lives of innocent, inoffensive men? Murdering thousands of them in their own land, by the hands of their own countrymen: Many thousands, year after year, on shipboard, and then casting them like dung into the sea! And tens of thousands in that cruel slavery, to which they are so unjustly reduced?

Of course, there were evangelical scholars who attempted to justify slavery, especially in the antebellum South. Some believed that reform was possible; others noted that the emancipation of slaves in the British Empire did not prevent an increase in human misery as Britain industrialised. However, Mark Noll notes that Christians who defended slavery in the Old South made a number of “illogical” moves which made their case untenable:

Of course, there were evangelical scholars who attempted to justify slavery, especially in the antebellum South. Some believed that reform was possible; others noted that the emancipation of slaves in the British Empire did not prevent an increase in human misery as Britain industrialised. However, Mark Noll notes that Christians who defended slavery in the Old South made a number of “illogical” moves which made their case untenable:

“[I]t was widely assumed that since Scripture did not condemn the institution as such, it thereby sanctioned the form of black-only slavery that prevailed in the United States. Countless works…causally transposed the terms “slaves” and “Africans” as if they were simply equivalent”

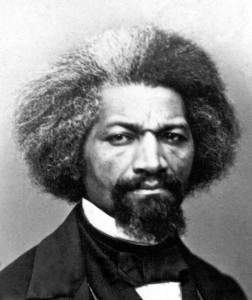

If every human is in God’s image, and Jesus died for every one, then every human is of equal worth in his eyes. If every person is descended from one family, and if everyone is marked original sin, then there is no room for racial pride. So the case against slavery in the British colonies and the Old South was at its strongest when it concentrated its fire on the cruel, callous racism which was at the very foundation of the institution. During the Civil War Frederick Douglass warned Northern abolitionists of limiting their campaign to the extinction of slavery:

“The law and the sword cannot abolish the malignant slave-holding sentiment which has kept the slave system alive in this country during two centuries. Pride of race, prejudice against color, will raise their hateful clamor for oppression of the Negro as heretofore. The slave having ceased to be the abject slave of a single master, his enemies will endeavour to make him an enemy of society at large.”

Unfortunately for the English speaking world, Douglass’s prophecy went unheeded. The injustices effected by the persecution of millions of Africans by white Europeans remain with us to this day. Contempt and hate have carved bitter wounds into geography, with millions of men and women seemingly excluded from prosperity merely because their ancestors had a particular colour of skin. So it would do the Church a great deal of good to return to the writings of the first abolitionists, to discover both what motivated them and how they argued for justice.

Unfortunately for the English speaking world, Douglass’s prophecy went unheeded. The injustices effected by the persecution of millions of Africans by white Europeans remain with us to this day. Contempt and hate have carved bitter wounds into geography, with millions of men and women seemingly excluded from prosperity merely because their ancestors had a particular colour of skin. So it would do the Church a great deal of good to return to the writings of the first abolitionists, to discover both what motivated them and how they argued for justice.

In any case, the abolitionists believed that biblical theology and faithful Church practice undermined the slave trade. I tend to agree with them; and we do them a great disservice if we think that they rejected their Christian inheritance, or the teachings of the Bible, to oppose inhuman bondage.