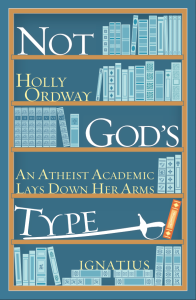

“Not God’s Type” is a crisp, wise and winsome autobiography, which retraces literary academic Holly Ordway’s steps from blind secularism to fulfilling faith. Her insights are invaluable for evangelicals for at least two reasons. Once she stood outside our subculture as an unchurchable secularist. Today, she is a non-evangelical working closely with evangelicals as Professor of Apologetics at Houston Baptist University. She understands the mind-set of the alienated unbeliever and has the viewpoint of a sympathetic outsider. This gives her a deep and penetrating perspective on where our evangelistic efforts go awry and on how our church culture has become impoverished of late.

Why was Ordway “not God’s type”? There was plenty of Christian outreach on the campuses where she studied. Well-meaning Christians even offered Ordway their friendship – if she would subject herself to their evangelism. Her problem was not a lack of opportunity to hear about God and the Gospel. The roots of problem ran deeper than that: she had been completely secularised by society and her education. Born-again Christians could not speak her language and she was not motivated to learn ours. Evangelical slogans about “accepting Jesus” made little sense to someone who had been raised outside the culture of the Church; to someone who believed that all faith was intrinsically irrational.

Why was Ordway “not God’s type”? There was plenty of Christian outreach on the campuses where she studied. Well-meaning Christians even offered Ordway their friendship – if she would subject herself to their evangelism. Her problem was not a lack of opportunity to hear about God and the Gospel. The roots of problem ran deeper than that: she had been completely secularised by society and her education. Born-again Christians could not speak her language and she was not motivated to learn ours. Evangelical slogans about “accepting Jesus” made little sense to someone who had been raised outside the culture of the Church; to someone who believed that all faith was intrinsically irrational.

To “accept Jesus in exchange for eternal life” sounded like an “impossible invitation”; it translated as “deny the evidence and God will reward you!” Which is absurd: you cannot make yourself believe what you know to be false. And what sort of God would leave no trace of himself in his creation? And then, to add injury to insult, punish us for not believing in him? Faith was a meaningless word, something for self-deluded fools or hypocrites, and a waste of time. Yet, Ordway was also vaguely aware that atheism left her unsatisfied.

Like most secularists, she assumed that the universe was simply a system of matter. She was also aware that if this universe was ultimately impersonal, then this universe was ultimately meaningless. She could not accept that all texts were meaningless language games (writing her doctoral dissertation on fantasy literature to escape fashionable literary theories). So, perhaps inconsistently, she believed that humans were capable of producing something meaningful. But this self-constructed meaning could only function as a stop-gap:

“…it is real only in the sense that a stage set of Elsinore Castle is a real place. One can suspend disbelief while Hamlet is being performed, but at some point, the curtain falls and one must leave the theatre.”

Human imagination is a powerful thing; but the idea that ephemeral human minds could impose meaning on the space-time universe seemed like so much wishful thinking to Ordway. Humanism divorced of religion offered no comfort either: humans are too insecure, too selfish and greedy, to fulfil anyone’s needs. Nor could romance or love offer salvation:

“…any couple relying exclusively on each other for all their fulfilment and meaning will surely drown, as Shakespeare says, like “two spent swimmers that do cling together/and choke on their art”.”

A secular age can only offer diversion and distraction from our existential needs. So Ordway turned to her career and her pastimes. She was not filled with despair; nor was she consciously seeking a religious experience. However, Ordway certainly suffered from the same incurable romanticism that afflicted CS Lewis: ‘senschucht’: a deeply felt, almost indefinable, nostalgic longing. Her spiritual desires expressed themselves in a love of fantasy; indeed, fantasy and old poetry prepared her heart for the gospel. CS Lewis, JRR Tolkien, the metaphysical poets and Gerald Manley Hopkins provided her with a thought world in which she could make emotional sense of the gospel.

Ordway was not reached through events or programmes. Instead, she found wisdom in a fencing instructor, who pressed her to reason through her objections to Christianity and to listen to his reasons for faith. He did not try to coerce a “decision for Christ”, and he gave her time to converse regularly with him and to think through his arguments. She was not rushed or harassed or bombarded with sound-bites and sermons.Rather, she was persuaded to follow Christ through dialogue, prayer and patience.

Travelling a path similar to the route I try to take readers down in New Atheism: A Survival Guide (a fact I found profoundly encouraging) first, she was convinced that theism made sense of the existence and moral order of the universe. Then she investigated the life of Christ, carefully sifting the historical evidence to see if his claims made sense. While she was on her intellectual journey she had a religious experience:

Travelling a path similar to the route I try to take readers down in New Atheism: A Survival Guide (a fact I found profoundly encouraging) first, she was convinced that theism made sense of the existence and moral order of the universe. Then she investigated the life of Christ, carefully sifting the historical evidence to see if his claims made sense. While she was on her intellectual journey she had a religious experience:

A Christian who has had a relationship with God for a long time might take this kind of experience for granted, so that it doesn’t seem like a big deal at all. But for me it was completely new, utterly unexpecte ….Everything felt sharp-edged, preternaturally clear; as if the very rocks and trees and sky were poised to reveal some meaning beyond themselves. I felt the presence of something, Someone, that was within me, yet outside or beyond myself. With a feeling something like dread, and certainly like fear, I recognised it for what it was: an experience of the Other.

This is the sort of experience which apologists often neglect. Now Ordway is clear: this was not a conversion experience; it did not indicate that she was in a saving relationship with God. But she had encountered God as something other than a hypothesis; she was no longer confronting an idea but a person. She did not fall prey to naïve experientialism; she treated the experience as extra data which gave weight and existential import to the evidence she had already considered. Quite correctly, it confirmed the truth of theism to her. Subsequently, careful examination of the evidence for the resurrection convinced her that Jesus had risen from the dead.

Theism made sense of her world: it explained why it appeared to be both beautiful and broken. God’s goodness is infinitely greater than ours; so we have turned away from him in our pride. Yet creation still points to, and reflects, a beautiful creator. But, choosing repentance towards God and faith in Jesus Christ is emotionally involving. It is not at all like adopting an academic theory or a personal philosophy. It is not an irrational existential leap either; Ordway needed to know whom she believed and why; and to be persuaded that he expected a commitment from her.

In this second edition of her book, Ordway explains why she left the Episcopalian Church for Roman Catholicism. I want to be circumspect; but I was not entirely convinced by Ordway’s reasoning, because she does not make her reasoning explicit. She clearly states that her journey was not primarily about weighing the evidence or considering the doctrinal issues. Becoming a Catholic was a paradigm shift in her thinking; and intuited sense of connection which unfolded over time. To list her reasons would not capture the emotional and intellectual essence of her journey:

It would be like falling in love by enumerating the outstanding qualities of the beloved: the list will contain things that seem utterly irrelevant to a third party, and will be both completely true and completely useless.”

She does offer some doctrinal defences of Catholic doctrine. For example, she critiques the principle of sola scriptura on the grounds that Church chose the canon of scripture. But no-one is suggesting that the church has no authority; even the lowest churchman would allow his elders to make some decisions. The point of sola scriptura is that scripture, and scripture alone, is the ultimate authority for God’s people, our final court of appeal. The decisions of the church must be overturned if they clash with the teaching of scripture; the revealed word of God must the foundation of the Churches decisions.

An evangelical would prefer to say that church councils merely recognised what should be canonical; after all, the church councils did write or edit the content of the books they collected. Nor could a council decide which books were widely recognised as authoritative. Furthermore, it is not so much written scripture but the inspired words of God which are authoritative. The word of God was spoken and heard before it was written. Jesus’ sermons were heard and memorised, preached and then recorded. Even epistles were dictated to a scribe: they were then read aloud to Churches, whose members were mainly illiterate.

It was the preached word which formed the church, as the apostles answered the call to rise up and follow Christ. Without the words of Christ the sacraments would not be mysterious but completely unintelligible. Whatever special authority Peter received – there is a chasm between Matthew 16 v 16-18 and the institution of the papacy- he received it through a spoken word. Logically and chronologically the word comes before the church. Humans were inspired to speak words from God; these were written so that the words could be heard in every generation; then the Church collected the writings. There is nothing in that chain that threatens sola scriptura.

For better or worse, then, I remain a convinced evangelical. Evangelical Christians may be tempted to skip the later sections of “Not God’s Type”; but this would be a mistake. They are not incidental to her argument. The entire book, particularly the thought provoking interludes, builds to Ordway’s decision to become Catholic. Crucially, she points to a deep flaw in evangelicalism. She is keenly aware that Jesus has been at work in this body throughout the generations. Every member of the body, past and present, is connected by a great web of prayer; hymns and prayers have been said throughout the world over centuries. Everyone who ever prayed that God’s kingdom would grow was praying for you.

Evangelicals simply ignore this aspect of the Church. We argue that our churches are sparse and our services simple because we want to recapture the simplicity of the early church. This is disingenuous hogwash; we reject tradition because we’re obsessed with relevance. We don’t do art and liturgy; but we will do drama and leisure centres. Whatever else occurs, we must be “contemporary”. Fashions spread like rumours through evangelicalism, and no one wants to be left behind. Our intentions are good – we want to reach the world and retain our own children. But Ordway’s story reveals three faults in our design.

First, we have not built bridges to the secular world; we have simply rebuilt our subculture in a more entertaining form. We do not appear fashionable, but smug, naïve and pietistic to outsiders. We do not realise that our message is incomprehensible to a culture which views faith as irrational and facts as the sole property of science. Ordway argues for the importance of apologetics because it is challenges the assumptions of the world and answers the questions of the sceptic. When we no longer defend our faith we suggest that we no longer care about the world or the sceptic. However, it would be more truthful to say that we do not reason with unbelievers because we no longer reason about what we believe.

Secondly, evangelicalism has obsessed with immediate, quantifiable results. Ordway’s conversion was not a simple, dramatic event; it was a long process, and her soul and mind were prepared for faith long before she knew what faith was. Too often we lack the patience required for such a journey. We look to business, marketing, and even engineering, to guide our churches. We talk about church growth, models of evangelism, and methods for preaching. We produce flow charts and check lists to teach us how to conquer our personal sins or how to talk to a neighbour about Christ. None of this has even the appearance of wisdom; it speaks to naïve, malnourished minds. Wisdom is only acquired through trust and endurance: by depending on Christ and growing in the knowledge of God; and it takes wisdom to reach the lost, not methodologies.

Thirdly, while jettisoning tradition made us more marketable, it also made us too light, too insubstantial to be taken seriously. Having lost our connection with the saints of the past, we lost our depth. We cannot sense that we are part of something more enduring than the next worship service, or the latest best-selling author. The church was planned in eternity past; the people of God have passed on His truth from generation to generation. But we preach as if the Christian message could be summarised in a few sound-bites. We act as if we were the first generation with Holy Scripture – as if the Church had no wisdom to pass on to its children.

We ought to stop worrying about product development and focus on what God has deemed important. I am not advocating traditionalism, intellectualism or elitism – or any “ism” for that matter. We should not go on a quest for academic or cultural respectability. There is no “ism”, no simple “how-to” guide which can provide the sort of growth the evangelical church needs. There is no substitute for faith in Christ humility before God. Together, these lead to wisdom. And, as Orway’s excellent work illustrates, wisdom is what all God’s people desperately need right now.