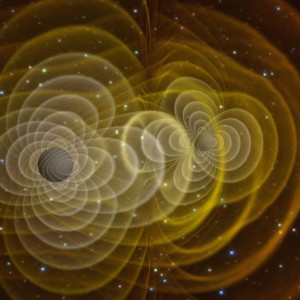

Image: Henze, NASA

Image: Henze, NASA

The recent detection of gravitational waves has received a lot of media coverage and rightly so for this is a remarkable finding from both an experimental and theoretical point of view. Gravitational waves are ripples in the fabric of space-time and were predicted by Albert Einstein 100 years ago. According to his general theory of relativity, accelerating massive object would radiate gravitational energy in the form of gravitational waves. However, since the effect is very weak, a very dramatic event is needed if there is to be any chance of detection. In this case it was the merging of two black holes, an event that took place over a billion years ago. Even so, by the time the waves reach Earth the distortion of space-time is less than the width of an atomic nucleus, which highlights just how astonishing a feat this is experimentally. While there had been indirect evidence for the existence of gravitational waves before, this was the first time they had been detected directly. As a bonus, it is also the first detection of two black holes merging and even the first direct detection of black holes themselves.

Does this have any relevance for belief in God? Of course, some people who think that science and religion are always in conflict will see this is another example of that. Science, they will say, can make these kinds of amazing predictions that are later verified by experiment, but religion hasn’t anything like that to offer at all. The suggestion is that science and religion should be contrasted and science chosen rather than religion.

But this is all wrong. It assumes that religion should be like science if it is to be taken seriously and, in particular, that it should make precise predictions that can be verified experimentally. Of course, a rather obvious point is that not all science works like this; but more importantly it is a simple category mistake to think of religion in this way. Treating religious belief as a sort of scientific theory and then showing that it isn’t as good as other scientific theories is just the wrong way to think about it. Disbelieving in God because religion doesn’t make mathematical predictions is a bit like not going to church because it isn’t as entertaining as going to see the latest blockbuster at the cinema. True, no doubt, but completely irrelevant.

So belief in God shouldn’t be contrasted with science. Instead it should be contrasted with naturalism. Naturalism is a worldview, which like belief in God and unlike general relativity, doesn’t make mathematical predictions. Now our question is whether the discovery of gravitational waves has any relevance for comparing belief in God on the one hand and naturalism on the other. There are at least two ways in which it might be relevant.

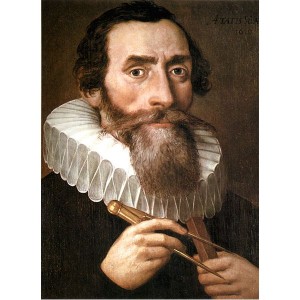

First, it is truly remarkable that a scientist, such as Einstein, sitting in his office working  on mathematical problems is able to make predictions that can be verified experimentally. Einstein and others sought for beauty or elegance in their equations and in doing so managed to uncover some of the mysteries of the universe. Why is the universe like that? Why can it be described so accurately using mathematics? Galileo had a clear answer to this question. He referred to nature as a book written by God, saying that ‘Mathematics is the language with which God has written the universe’. And of course that means we need to use mathematics in order to read the book. In other words, the mathematical nature of the universe is explained in terms of its creation by an intelligent Mind and we (or at least Einstein et al) are able to comprehend it by using our minds. To use Kepler’s phrase, we are ‘thinking God’s thoughts after him’. For more on why theism provides a better explanation than naturalism of this feature of the universe see Evidence for God: Design (Part 1 – Order in the Cosmos) and The Argument from Maths in Seven Quick Points.

on mathematical problems is able to make predictions that can be verified experimentally. Einstein and others sought for beauty or elegance in their equations and in doing so managed to uncover some of the mysteries of the universe. Why is the universe like that? Why can it be described so accurately using mathematics? Galileo had a clear answer to this question. He referred to nature as a book written by God, saying that ‘Mathematics is the language with which God has written the universe’. And of course that means we need to use mathematics in order to read the book. In other words, the mathematical nature of the universe is explained in terms of its creation by an intelligent Mind and we (or at least Einstein et al) are able to comprehend it by using our minds. To use Kepler’s phrase, we are ‘thinking God’s thoughts after him’. For more on why theism provides a better explanation than naturalism of this feature of the universe see Evidence for God: Design (Part 1 – Order in the Cosmos) and The Argument from Maths in Seven Quick Points.

Second, the discovery of gravitational waves provides additional confirmation of Einstein’s theory of general relativity. It has already been well confirmed in many other ways, but this new evidence (which Einstein thought would be undetectable) makes the case even stronger and further establishes its incredible accuracy. Why is this relevant? Modern cosmology, including the big bang, is based on Einstein’s theory. In particular, various technical results pointing to the universe having had a beginning are based directly on general relativity. While none of this constitutes proof of a beginning, the evidence strongly suggests it and this additional confirmation of general relativity only serves to make the case stronger still. If this is correct, it sits very neatly with belief in God and very uncomfortably with naturalism.

One final point is that unfortunately many Christian young people do falsely perceive a conflict between belief in God and science along the lines mentioned earlier. This could be because that is the impression that has been given by Christian leaders or by the media or by vocal proponents of atheism. But there really isn’t any good reason to fear science or to think that amazing scientific discoveries like this somehow pose a problem. Instead Christian young people should be encouraged to engage in science and to recognize, as Kepler and Galileo would, that this kind of breakthrough gives us another insight into the genius of the Creator of the universe.