It’s December, the season typically known for its Christmas bells, nativity plays and general good cheer. Frosts deepen, children count down the days before Christmas and parents puzzle how to turn a bath towel into a realistic Joseph. Or do they?

During a conversation with friends this morning, it struck me that in the last 12 years of attending school Christmas plays with my children, I have not seen a single traditional nativity story enacted for us parents. Gone, seemingly, are Mary, Joseph and the baby Jesus; in their place reside grumpy sheep, bashful fairies and the odd lost Christmas light searching for its sparkle. What are we to make of it all? Is the Christmas story simply a bygone myth, a quaint story of yesteryear that has served its purpose, of no more relevance to the 21st century than the Greek myths of long ago?

During a conversation with friends this morning, it struck me that in the last 12 years of attending school Christmas plays with my children, I have not seen a single traditional nativity story enacted for us parents. Gone, seemingly, are Mary, Joseph and the baby Jesus; in their place reside grumpy sheep, bashful fairies and the odd lost Christmas light searching for its sparkle. What are we to make of it all? Is the Christmas story simply a bygone myth, a quaint story of yesteryear that has served its purpose, of no more relevance to the 21st century than the Greek myths of long ago?

The charge that the gospel accounts of Jesus’ life and death have been borrowed and adapted from earlier pagan mythic sources is one often levied against Christianity. Its proponents point to apparent lines of convergence between the gospel stories and ancient myths, and conclude that, since the Greek myths pre-date the claims of the early church, these must be the authentic material from which the Christian writers sought their inspiration.

“Muthos” , the ancient Greek word for “story or narrative”, is the linguistic root from which our English word “myth” derives. Originally it meant simply that, a story or narrative; only later did it begin to take on the connotations we attribute to it today, of “fable, fiction or lie”. This explains why C S Lewis was able to refer to Christianity as “God’s myth”; he was attributing to the word its original and precise meaning, although this has at times been misunderstood by a later reading public. When Lewis employed the category of myth, he intended us to understand this as “true myth”, a true, narrative account of an actual happening.

By the time of the early church, however, myth had begun to adopt the characteristics we lend to it today, of fiction and make-believe. The distinction between truth and fiction was real enough to Paul, who warns Timothy to “have nothing to do with irreverent, silly myths” (1 Tim. 4:7) while the writer of 2 Peter clearly differentiates between truth and falsehood when he writes “we did not follow cleverly devised myths when we made known to you the power and coming of our Lord Jesus Christ, but we were eyewitnesses of his majesty.” Clearly, this writer believed in the absolute truth of what he proclaimed; he had both seen and experienced the power and resurrection of Jesus in time-place history and is concerned to draw a clear line of demarcation between myth and truth in his statement.

Myths contain several well-defined characteristics that make then recognisable as myth. Central to these is the primordial struggle between good and evil, epitomised in the journey of the hero who battles against these forces threatening the order and well-being of the cosmos. Usually present is a heavenly realm, home to the gods, paralleled by an underworld where forces of darkness dwell. The hero, as he journeys, will encounter dragons, opposition and dark forces; his cosmic battle even taking him into the bowels of the underworld as he defies the forces of death itself, emerging victorious to continue his quest. For those familiar with the early Christian narratives of the life and sacrificial death of Jesus for the sins of the world, there may indeed seem to be surface similarities between the two sources.

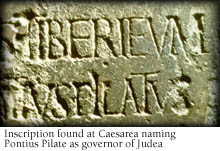

I would suggest however that these similarities are superficial only; there remain crucial, unresolved differences that place the gospel accounts on a completely different footing from their mythic counterparts, differences which should not be overlooked. Central and crucial to these is the historic nature of the gospel narratives. Each of the four gospel writers goes to great lengths to give us precise geographical and historical markers for the life and times of Jesus. Greek heroes by contrast, are universal; timeless figures transcending ordinary time and place. Jesus, however, is “Jesus from Nazareth” a small village we know was situated to the far north of Judea in Galilee. He is firmly placed in his historical setting, a Galilean Jew, born around the beginning of the first century (between 6 and 4 BC) and dying between 30 and 36 AD in Judea, under the orders of the Roman governor Pontius Pilate, who held office from 26-36 AD. Luke and Matthew both include precise, detailed genealogies, emphasising his human lineage, and anchoring him absolutely in his Jewish, Palestinian historical context. Luke 3:23 states that Jesus “was about thirty years old” at the start of his ministry, which according to Acts 10:37 & 38 was preceded by John’s ministry, itself recorded by Luke ( 3:1) to have begun in the 15th year of Tiberius’ reign (28 or 29 AD). There is nothing ambiguous or transcendent about these details: Jesus was a real man who lived and died in real history.

I would suggest however that these similarities are superficial only; there remain crucial, unresolved differences that place the gospel accounts on a completely different footing from their mythic counterparts, differences which should not be overlooked. Central and crucial to these is the historic nature of the gospel narratives. Each of the four gospel writers goes to great lengths to give us precise geographical and historical markers for the life and times of Jesus. Greek heroes by contrast, are universal; timeless figures transcending ordinary time and place. Jesus, however, is “Jesus from Nazareth” a small village we know was situated to the far north of Judea in Galilee. He is firmly placed in his historical setting, a Galilean Jew, born around the beginning of the first century (between 6 and 4 BC) and dying between 30 and 36 AD in Judea, under the orders of the Roman governor Pontius Pilate, who held office from 26-36 AD. Luke and Matthew both include precise, detailed genealogies, emphasising his human lineage, and anchoring him absolutely in his Jewish, Palestinian historical context. Luke 3:23 states that Jesus “was about thirty years old” at the start of his ministry, which according to Acts 10:37 & 38 was preceded by John’s ministry, itself recorded by Luke ( 3:1) to have begun in the 15th year of Tiberius’ reign (28 or 29 AD). There is nothing ambiguous or transcendent about these details: Jesus was a real man who lived and died in real history.

External sources, as well as the gospel accounts, place Jesus in this same historical/geographical setting. Both the Roman historian and senator Tacitus (Annals, a history of the Roman Empire from the reign of Tiberius to that of Nero, AD 14-68) and the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (Antiquities of the Jews) speak of Jesus. Both men were credible, well-regarded historians giving us no reason to doubt their locating Jesus in the same context as that of the gospels.

There remains a deeper, more fundamental consideration however; Judaism, from which Christianity takes its theological roots, was, (and still is), a fiercely monotheistic religion. It has clung tenaciously, nearly always in the face of wide-spread cultural opposition, to the idea of there being “one God and one God only”. This fierce monotheism encapsulates the monotheistic essence of Judaism, lying central to its identity and self understanding; “Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One” being the twice daily Shema, the call to worship that has shaped the devotional life of observant Jews down through the centuries. The Greek myths, on the other hand, are unashamedly polytheistic; they contain stories of multiple gods, from Mithras, Attis, and Orpheus, Greco-Roman deities, to the mystery cult deities of Dionysus and Osiris. No observant Jew would have had entertained for a moment the Greco-Roman polytheism inherent in these myths. To think that they would have, is both theologically and historically inconceivable, and betrays a mind unschooled in both history and theology.

There remains a deeper, more fundamental consideration however; Judaism, from which Christianity takes its theological roots, was, (and still is), a fiercely monotheistic religion. It has clung tenaciously, nearly always in the face of wide-spread cultural opposition, to the idea of there being “one God and one God only”. This fierce monotheism encapsulates the monotheistic essence of Judaism, lying central to its identity and self understanding; “Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One” being the twice daily Shema, the call to worship that has shaped the devotional life of observant Jews down through the centuries. The Greek myths, on the other hand, are unashamedly polytheistic; they contain stories of multiple gods, from Mithras, Attis, and Orpheus, Greco-Roman deities, to the mystery cult deities of Dionysus and Osiris. No observant Jew would have had entertained for a moment the Greco-Roman polytheism inherent in these myths. To think that they would have, is both theologically and historically inconceivable, and betrays a mind unschooled in both history and theology.

Yet what are myths, after all? Are they not the stories of the heart; the imaginative impulse let loose upon this world? Should it really surprise us that the myths deal with the universal questions of mankind: “Is there an afterlife, are good and evil rewarded or recognised in the heavenly realm, is there a “hero” big enough to save us from the complexities and challenges of life? Is there One we can follow who knows the way?” These are the questions of humanity because humanity is made in the image of God: these are God’s question; the ones he means us to quest after and find answers to. Myths are the attempts of men and women to answer these questions, the universality of the quest reflected in the universality of the questions. Lewis would remind us

not to be ashamed of the mythical radiance resting on our theology. We must not, in false spirituality, withhold our imaginative welcome….For this is the marriage of heaven and earth. Perfect Myth and Perfect Fact: claiming not only our love and our obedience, but also our wonder and delight.” 1

If we see life as heavily compartmentalised, the sacred imprisoned from the secular, as 21st century scientism has so often encouraged us to do, there will be no room in our thinking for the concept of “true myth” I would suggest however, that the fault lies not in the limitation of the concept but in the limitation of our thinking. Accurate facts tell the most compelling stories, for it is when the imaginative impulse works with, and compliments, the powers of reason that the pursuit of truth is best served. Where would science be without the imagination to probe the unknown? What danger, verging on madness, the imagination would be in, if it did not have some undeniable facts to anchor it to the world of reality! “True myth” is not a contradiction in terms; it is the unmistakable rhythm of this world. C.S. Lewis saw this clearly when he wrote, “Now the story of Christ is simply a true myth: a myth working on us the same way as the others, but with one tremendous difference – that it really happened: and one must be content to accept it in the same way, remembering that it is God’s myth where the others are men’s myths: i.e. the Pagan stories are God expressing Himself through the mind of the poets, using such images as he found there, while Christianity is God expressing himself through what we call “real things”.” 2

As Lewis’ friend Tolkien said,

This story is supreme; and it is true.” 3

Works Cited

- Lewis, C. S. “Myth Became Fact.” In God in the Dock: Essays on Theology and Ethics, by C. S. Lewis, edited by Walter Hooper, 63–67. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1944/2001.

- Ibid

- Tolkien, J. R. R. “On Fairy-stories.” In Tree and Leaf, by J. R. R. Tolkien, 11–70. London: Unwin Books, 1947/1964/1970.