Centuries from now, anthropologists sifting through cultural artefacts might conclude that Christmas was a time of year when people of different faiths came together to worship Santa. After all, everyone loves the patron saint of pester power, excessive consumerism and Coca-Cola. And, when we set cynicism aside and forget the strain placed on our credit cards each December, we all value Saint Nick as a symbol of imagination and child-like wonder. Little wonder, then, that American Atheists have recruited Santa to run their traditional Yule-tide publicity campaign.

Haunted by the fear that someone, somewhere might be enjoying a Nativity play or Christmas carol, every year American Atheists remind us that radical secularists can also enjoy Christmas. Festive cheer can be achieved, it seems, by pouring ill-informed scorn on anyone who doesn’t share your naïve dogmatism.

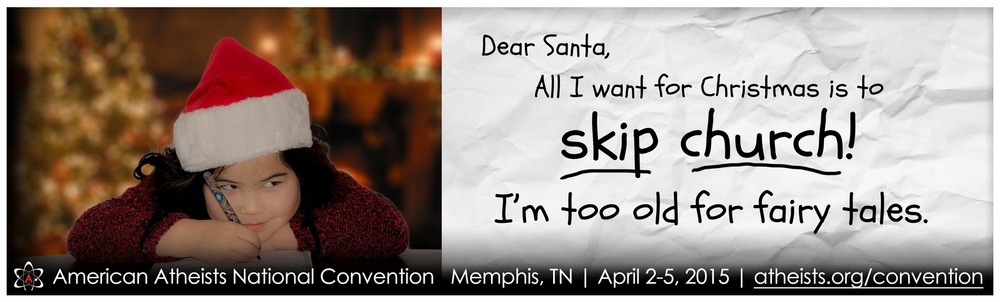

Last year’s billboard displayed a free-thinking pre-teen writing to Santa for permission to dodge church. This year, Santa wrote back. It seems that we all have Santa’s permission to skip church so long as we promise to be good; though Santa also stipulates that we be good for the sake of goodness.

Last year’s billboard displayed a free-thinking pre-teen writing to Santa for permission to dodge church. This year, Santa wrote back. It seems that we all have Santa’s permission to skip church so long as we promise to be good; though Santa also stipulates that we be good for the sake of goodness.

So Santa does not approve if we behave out of self-interest or religious motives. Who would have thought that Father Christmas could be so puritanical? We might also ask where this “goodness”, which so enamours Santa, resides. In the human heart? Hardly. Goodness cannot be generated by sub-atomic particles or physico-chemical laws. If we are nothing more than atoms and molecules in motion, then the “human heart” is a sentimental fantasy; it is as concrete as Santa’s workshop.

But even if we reject the physicalism of our age, and acknowledge that human consciousness is substantial and significant, the human heart cannot be source of “goodness”. If any philosopher believed that humans should be good out of respect for goodness alone, it was Immanuel Kant. But Kant cautioned that we cannot put our faith in the human spirit because humans are constructed of “crooked timber”. Our motives and purposes are rotten. We cannot even want to do what we know we should do.

The problem, which escapes American Atheists, is that we all struggle to be good for anything’s or anyone’s sake. Any moral standard built merely with human resources is bound to fail. We have not discovered a simple, plausible moral code which we will not repeatedly and deliberately broken. In our desires and deeds we break the spirit and the letter of every moral law. So “goodness” cannot be created, sustained or achieved by human consciousness.

Is religiosity the solution? “We want people to know that going to church has absolutely nothing to do with being a good person,” said Mr Silverman, President of American Atheists. Perhaps next year he will update us on the Pope’s preferred Christian denomination. Christians are already aware of Jesus’s vicious attacks on religious legalism and Paul’s rigorous critique of pride based on religious deeds. The Church cannot make us good according to those who founded it.

So what is goodness? How can we find and achieve it? A religious philosopher might reply that God is the greatest good because he is, as a matter of brute fact, the most valuable thing in existence. If everything else depends on God for its existence then the value that God has for everything else cannot be surpassed. God is supremely rational, and his power cannot be limited by the irrational and chaotic effects of evil. The earth and the opinions of human beings will pass away into the void. God’s values are eternal. His judgements can be trusted, and his worth is inestimable.

Put another way, goodness is personal. It is not an abstract metaphysical substance which dwelling beyond time and space. If it were humans could casually disregard it (and many might be happier for doing so). But goodness is intimately connected with creation; it sustains the universe and brought it into being. Goodness knows us intimately and loves us infinitely. And the Bible summarises all this in three profound words: God is love.

But how can we be good? And how could we ever be morally fit for fellowship with infinite love? By following the way, the truth and the life. In love, we can take responsibility for another’s failures if that person is in fellowship with us. A parent can accept the consequences of a child’s actions; an officer can make himself accountable for the actions of the men under his command. The Son of God became one of us in love, and was broken in our place, so that our crookedness could not keep us from coming to him.

We do not celebrate Christmas to be good because religious deeds cannot make us good. We cannot make ourselves good because we lack the will and wisdom. But God can consider us good if we are united to him by depending on him. Then God’s love will transform us to be good both for his sake and for the sake of everyone else he loves. We celebrate Christmas, then, out of love for God and others. Skip the Christmas service if you like; you will not have broken a single commandment. But don’t neglect God the Son who came and suffered and died for your sake.