There are two ways of conceiving God’s relationship to time: God could be everlasting or timelessly eternal. God would be everlasting if he has a beginningless and endless existence in time. God would be timelessly eternal if no duration ever occurs in his life; if he has no extension or location in any time whatsoever. If God is timelessly eternal, then God’s life would be total simul: that is, he would have it all at once (Taliaferro, 1998, p.145-147). God’s would possess the whole of his life together.

Aquinas argued that God is timelessly eternal and that time is present “all at once” to God. Aquinas uses the image of the circumference and centre of a circle. The centre of the circle is not part of the circumference, so it is “outside” the circumference. Yet all of the circumference is “present” to the centre. God’s eternity is like the centre of the circle – he is outside time, yet all of time is present to him. This view of God’s relationship to time has been challenged increasingly in recent years. This essay will ask if the challenges have any merit.

Aquinas argued that God is timelessly eternal and that time is present “all at once” to God. Aquinas uses the image of the circumference and centre of a circle. The centre of the circle is not part of the circumference, so it is “outside” the circumference. Yet all of the circumference is “present” to the centre. God’s eternity is like the centre of the circle – he is outside time, yet all of time is present to him. This view of God’s relationship to time has been challenged increasingly in recent years. This essay will ask if the challenges have any merit.

The article’s structure is as follows: Section 1 will define key terms essential to understanding the central argument of the essay . Section 2 will briefly consider the chief argument for God’s timeless eternality. Section 3 will give the article’s central argument: that on the process conception of time God cannot be timelessly eternal. Section 4 argues that the process view of time is more plausible than the alternative. The article concludes that there is reason to think that God is not timelessly eternal.

However, it should be noted that there is significant room for disagreement between Christians on this point; for an alternative view I recommend Lydia McGrew’s article Before the Mountains Were Brought Forth: A Defence of Divine Timelessness.

- 1. Definitions of key terms

Following Padgett (1992, p.1-17), we can set out the definitions of some key terms. Time can be thought of as a series of durations. A duration is a period of time bounded by instants. Instants are durationless points of time. An object will refer to a particular continuant and a change is a happening which makes a difference to an object. Two objects, or two states of one object, cannot be the same if they do not have all their properties in common. An object can have certain properties independently of its relationships to all other objects: the roundness of a ball does not depend on the ball’s relationship to any other object or event. These properties are referred to as qualitative properties.

Other properties are relational properties. A ball’s weight will depend on its relationship to some particular gravitational field; being an uncle or a husband depends on one’s relationships to other humans. We can then distinguish between two types of change: qualitative change and relative change. A change is qualitative if some quality is gained or lost; a change is relative is some relational property is gained or lost.

All qualitative changes are real changes; a relative change in an object is only a real change if some qualitative change has taken place in an object which is the basis of the relative change. Xanthippe’s becoming a widow is a relative change between her and Socrates, but it occurs because a qualitative real change has occurred in Socrates (he has died). We cannot reduce talk about time to talk about change; but while time is not identical with change it is contingent upon it. Necessarily, if no duration occurs, no change can occur. It follows that, necessarily, if a change occurs then a duration occurs.

All qualitative changes are real changes; a relative change in an object is only a real change if some qualitative change has taken place in an object which is the basis of the relative change. Xanthippe’s becoming a widow is a relative change between her and Socrates, but it occurs because a qualitative real change has occurred in Socrates (he has died). We cannot reduce talk about time to talk about change; but while time is not identical with change it is contingent upon it. Necessarily, if no duration occurs, no change can occur. It follows that, necessarily, if a change occurs then a duration occurs.

All events can be ordered in terms of some being present, some being past and some being future; following J.M.E McTaggart, we can call this way of ordering events the A series. All pairs of events can also be ordered so that they are either simultaneous, or one event precedes the other. McTaggart called this way of ordering events the B series. These distinct ways of ordering temporal events have led to different conceptions of temporal becoming.

On a stasis or B-theory, all moments of time are equally existent and are connected as ‘before’, ‘after’ or ‘simultaneous’. The distinctions between “past”, “present” and “future” are not objective distinctions: these distinctions depend on subjective consciousness. A comparison with spatial concepts like here and there illustrates the point. Terms like here and there do not mark an objective distinction in space. Whether or not some particular location is here or there depends on one’s conscious experience and the location of one’s body in relation to other physical objects. In the absence of embodied conscious beings terms like “here” and “there” would be entirely meaningless.

On the stasis theory of time each of our actions has a particular objective location in the B series of time; whether or not an event is “present”, “past” or “future” depends only on our consciousness of our location in the B series. Terms like “now”, “then”, “past” and “present” are meaningless in the absence of agents and their actions. They merely describe how the B-series appears from the perspective of particular agents. For agents located in the year 1814 events in the year 2014 are future; for agents located in 2014 the events of 1814 are past. But 1814 and 2014 are both for the exponent of the stasis theory of time equally ontologically, objectively real.

The import of the stasis view is that there is no objectively real past, present or future: the four-dimensional space-time universe exists as a block (Craig and Moreland, 2003, p.379). Padgett quotes stasis theorist D.H Mellor

What exists cannot be limited to what is present, or present and past, because the restriction has no basis in reality. The world can neither grow by the accretion of things, events or facts as they become present, nor can increasing pastness remove them (Padgett, p5)

“A-theories” or “process” theories of time are committed to the objective reality of temporal becoming. Things go in and out of existence as time elapses. The flow of time is ontologically real on a process theory: it would occur even if there were no human agents to observe its occurrence. The difference between past, present and future refers to an difference in ontological status.

A process theory of time implies “presentism”: the doctrine that the only temporal entities that exist are those occurring in the present (Craig and Moreland, 2003, p.388). When an event occurs it is present; the fact that an event did occur is very different from its now occurring. An event which occurred in the past no longer continues to occur: its occurring is over. It is only objectively real in the sense that it can be a component of complex facts: that is to say, we can refer to it, have true or false beliefs about it and so forth (Wolterstorff, 2001, p.196).

A process theory of time implies “presentism”: the doctrine that the only temporal entities that exist are those occurring in the present (Craig and Moreland, 2003, p.388). When an event occurs it is present; the fact that an event did occur is very different from its now occurring. An event which occurred in the past no longer continues to occur: its occurring is over. It is only objectively real in the sense that it can be a component of complex facts: that is to say, we can refer to it, have true or false beliefs about it and so forth (Wolterstorff, 2001, p.196).

- 2. The case for timeless eternality

Those who defend God’s timeless eternality typically argue that if God is a perfect being, then God would be free from the limits of change and temporality. Any life which exists in time, and has a past, a present and a future, lacks perfection. Our pasts contain many events which we would like to relive, but which are forever lost to us. We may anticipate many events which are yet to occur.

On balance, each part of a perfect being’s life would be good. So if God was not currently living a part of his life – because it was in his past – then God would have lost a good part of his life. Indeed, given that God has no beginning God would have lost infinitely many goods. It is difficult to see how this loss could be compensated for. A perfect being could not allow himself to lose goods in this way.

To many, the idea that God is subject to the vicissitudes of temporal passage, with more and more of his life irretrievably over and done with, is incompatible with divine sovereignty, with divine perfection and with the fullness of being that is essential to God (Helm. 2001, p.30-31)

However, Padgett (2001, p.62) insists that God could be immutable in his basic attributes; he could not lose omnipotence or omniscience, so it is not fair to characterise God as being subject to the “vicissitudes” of time. (Padgett, 2001, p.62). Nicholas Wolterstorff points out that the experience of a timelessly eternal God would be unchanging, and pointedly asks:

…why would anyone imagine that unchanging experience, be it momentary or durational, is a more excellent form of life – or if you will, fuller- than that which I do experience? …To me it seems just bizarre to suppose that such a life would be more excellent, more full. It seems on the contrary, appallingly impoverished. Change, and the changing experience of change, makes possible a fullness in the totality of one’s life experiences that would be impossible without change. One cannot possibly pack all that’s rich and excellent in experience into one unchanging state; it needs to be strung out over time (Wolterstorff, 2001, p.73).

Moreover, God’s perfect, intimate and exhaustive knowledge of the future means that God would not experience time as we do. Nothing would be lost to him through forgetfulness, for example.

It seems, then, that philosophers and theologians have conflicting intuitions over what would constitute perfect fullness of life. There is no straightforward argument from divine perfection to divine timelessness.

- 3. An argument that God could not be timelessly eternal

A central doctrine of Christian theism, which preserves God’s immanence within creation and transcendence over creation, is that the universe would not exist if God did not act to sustain the universe at each moment of its existence. God causes the laws of nature and the basic pessays or fields of the universe; furthermore, God is the essential cause of the essential properties that each object has at each moment of its existence, and God causes each object to continue to exist so long as it exists (Padgett, 1992, p.19-20).

God’s causing the universe to continue to exist would be a direct act and zero time related to its effect. No duration would occurs between the cause and the effect; God is not limited as physical things are, and there is no causal chain between God and the most fundamental constituents of his creation (Padgett, 1992, p. 20-21). Now, the occurrence of an effect (which is itself a change) implies a change in some cause of the effect (Padgett, 1992, p.60). If a light suddenly goes on or off, something has changed in the causes of the light.

If the process theory of time is true then the world is an everchanging reality. Bringing something into existence, or ceasing to sustain something, entails a real change in the creator. As God’s actions change, God changes (Padgett, 1992, p. 63). These would be a real changes in God, not merely relative changes. God would exercise his causal power in different ways to sustain different objects; doing different things at different times entails a qualitative change in an agent (Padgett, 1992, p.60).

We must recall that the future and the past do not exist on the process view; so God can only bring about the effects of his actions in the present, and must wait for the present to occur if he is to act on real existent things. If the process theory of time is true, then things and events change their ontological status with the passage of time. Since God sustains every thing and every event, real changes must take place in God over time. In section 1 we pointed out that if a change occurs then a duration occurs. Time is a series of durations. Since a series of changes occur in God as he sustains a changing universe, God must undergo a series of durations, and therefore God is not timeless.

Paul Helm and Nicholas Wolterstorff (2001) have objected to Padgett’s argument on these grounds: if God is an atemporal being then God could atemporally will ( that is without change in himself) a sequence of effects in time. They both refer to Aquinas’ argument that newness of effect does not entail newness of action in God. To ‘act’ is to “bring about something as the result of intending or desiring that thing, and to do so for a purpose” (Helm, 2001, p.53). Wolterstorff points out that we must distinguish between the time of one makes a decision to bring an event about and the time one decides that the event should occur (Wolterstorff, 2001, p.121). One could act at 8pm to set a thermostat to come on at 9pm. The time of the decision to bring about the event would be separated by one hour from the time one decided the event should occur. So one could act at 8pm to bring about an event at 9pm. It follows, according to Helm and Wolterstorff, that there is nothing incoherent about God timelessly willing an event to occur at some particular time. God could timelessly decide that an event, E, will occur at a time, T.

Padgett, however, believes that this missed the point of his argument. We can mean several things by the term “will”, and these meanings should be carefully distinguished. If we mean “plan” or “intention” by will, then God’s will does not need to change with a changing creation. If God’s foreknows the future, God’s will could indeed remain unchanging. It is coherent to suppose that could have willed certain events occur at certain times, and that he willed this before the world began. It is also, then, coherent to suppose that God could timelessly will that certain events take place at certain times (Padgett 2001, p.125)

However, “will” also bears another meaning. “Will” can also mean to “choose to act”; to exercise one’s causal power(Padgett, 1992, p.63-65; Padgett 2001, p.125) To accomplish anything an agent must exercise his ability to bring about the intended effect:

If I always have the power to raise my arm, and I design to do it at a particular time X, I must also add the intention to raise my arm at time X. We shall call this ability to bring about an intended effect one’s “power-to-act”. In order to act any agent must use or put forth power-to-act, or cease to do so for those effects one wishes to stop (Padgett, 1992, p.64)

God must act to sustain every state of the universe; if the states of the universe are different, God is acting differently. God cannot act once, changelessly, to sustain a changing world if the process theory of time is true. To see this a little more clearly, consider: humans can try to exercise their “power-to-act” and fail. So, I might try to stand up and walk, yet fail if I have a spinal injury which has taken away the use of my limbs. God, being omnipotent, cannot try and fail. If God exercises his “power-to-act” he always succeeds. God cannot timelessly and changelessly exercise his power-to-act so that event E occur at future time F because, on the process view, E-at-F does not exist. Yet if God had exercised his power to act, then E-at-F could not fail to exist (Padgett, 1992, p.65-66).

This argument only works if the process theory of time is true. However, Padgett, Wolterstorff and Helm are agreed on this point: if the stasis theory of time is true, then an atemporal God could changelessly will a “changing” universe. This is because things and events do not change their ontological status on the stasis theory of time; on the stasis theory E-at-F is as real as any past or present event. Therefore, God could act timelessly to bring about E-at-F. If God is timelessly eternal the stasis theory of time must be true. So, if we have good reason to think that the stasis theory of time is false then we have good reason to believe that God is not timelessly eternal.

However, if the stasis theory of time is false, God’s relationship to time would still be rather different from ours. Padgett points out that God would be relatively timeless (Padgett 1992, 127-129). The law-like regularities of the universe are essential to measuring time: they allow for the regular processes which underlie clocks. But God is not subject to the laws of nature; nothing could cause him to repeat the same action over and over with great regularity; nor is there is anything in eternity which could act as a measure of God’s activity.

However, if the stasis theory of time is false, God’s relationship to time would still be rather different from ours. Padgett points out that God would be relatively timeless (Padgett 1992, 127-129). The law-like regularities of the universe are essential to measuring time: they allow for the regular processes which underlie clocks. But God is not subject to the laws of nature; nothing could cause him to repeat the same action over and over with great regularity; nor is there is anything in eternity which could act as a measure of God’s activity.

Couldn’t we use the activity of this universe to measure God? Suppose God sustains two episodes of some object, E1 and E2. Say further that there is exactly one “Stund” between E1 and E2, a Stund being a measure of cosmic time based on the flow of fundamental particles. If God’s activity and life is sometimes simultaneous with our time, doesn’t the clock of our universe measure God’s life in some way? Since God must exist with E1 and E2, and they are one Stund apart, doesn’t it follow that God lived for one Stund?

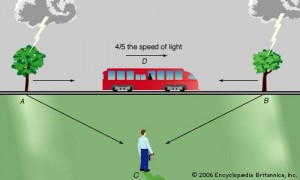

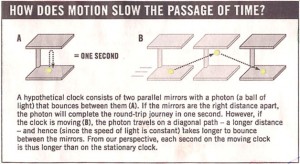

The problem here is that we cannot make assumptions about God based on what God seems like from our own temporal reference frame. In fact, an observer in this universe moving at a velocity near the speed of light in her own reference frame would not measure the duration between E1 and E2 as one Stund. So the measured time system of our universe would have little – if any- meaning when applied to anything outside this universe. We can infer that the act which sustained E1 came before E2, but little else (Padgett, 1992, 128). So, while God would be temporal, he would not be in “Measured Time”. Along with his exhaustive, intimate knowledge of all events in our present and past, it is clear that God transcends time as humans experience and measure it.

The problem here is that we cannot make assumptions about God based on what God seems like from our own temporal reference frame. In fact, an observer in this universe moving at a velocity near the speed of light in her own reference frame would not measure the duration between E1 and E2 as one Stund. So the measured time system of our universe would have little – if any- meaning when applied to anything outside this universe. We can infer that the act which sustained E1 came before E2, but little else (Padgett, 1992, 128). So, while God would be temporal, he would not be in “Measured Time”. Along with his exhaustive, intimate knowledge of all events in our present and past, it is clear that God transcends time as humans experience and measure it.

- 4. The stasis theory of time considered

One argument for the stasis theory of time is that all tensed or process facts can be reduced to tenseless or stasis facts (Padgett, 2001, p.100-106). A fact will be construed as whatever makes a sentence true or whatever satisfies truth conditions. It is arguable that process facts cannot be reduced to stasis facts. Given our specific dating system we can specify every moment in time. We can give the true date for whatever moment happens to be present in this system. The true date will change as different dates become present. “It is presently 23rd November 2014” is a tensed or process fact.

Can this tensed fact be reduced to a tenseless fact? Some stasis theorists have argued that:

(1) “It is presently 23rd November 2014”

is equivalent to

(2) “It is 23rd November 2014 on 23rd November 2014”

However, these two sentences do not report the same fact. 2 is always true; 1 is only true on one particular date. If we know it is true that “It is 23rd November 2014 on 23rd November 2014” we do not know that it is also true that it is now 23rd November 2013.

The key here is to remember that “now” does not denote some date simultaneous with its utterance in a sentence. To say that time “‘T1’ is now” is to predicate a quality of the moment picked out by T1: that T1 is present. By way of contrast, it is always true that “T1 is simultaneous with T1” (Padgett, 1992, p. 104). Furthermore, the propositions asserted by tensed and tenseless sentences have different entailments. If I say “I began this essay two days before now”, I entail nothing about the date I started this essay. If I say, “I started this essay on 21st November 2014”, I entail noting about how long ago that was.

Can the truth conditions of tensed sentences be reduced to the truth conditions of tenseless sentences? Take the sentence token: “Today is the 24th November 2014”, which can be given the normal, Tarski truth condition

A “Today is the 24th November 2014”, is true iff today is 24th November 2014

Stasis theorists such as DH Mellor have argued that this can be given a tenseless truth condition:

B “Today is the 24th November”, is true iff the utterance of that token is simultaneous with 24th November 2014

However, it is very plausible that two different truth conditions are equivalent if and only if they state the same fact: that is, if they attribute the same properties to the same thing(s) in the same time and place (Padgett, 1992, 105-106). A and B do not attribute the same properties to the same thing(s) in the same time and place. B attributes simultaneity of a date with an utterance. A has a different object and a different property –today being the 24th November (Padgett, 1992, p. 105-106). It is not at all clear that B gives the truth conditions of A. In any case, B fails to give the meaning or the content of “today is the 24th November 2014”, and what we require from the stasis theorist is a tenseless account of the meaning and content of tensed sentences (Wolterstorff, 2002, p. 199; Craig and Moreland, 2004, p. 382-383).

So stasis theorists seem unable to reduce tensed facts to tenseless facts; tensed facts, it seems, do not supervene on, and cannot be reduced to tenseless facts. This strongly suggests the reality of tense or temporal becoming. Our belief in the real distinctions between past, present and future seems basic; the presentness of experience seems undeniable. The experience of tense should be considered veridical unless we have some strong reason to deny it (Craig and Moreland, 2004, p.380-381) and no strong reason has been found. If the static theory of time is true the universe only seems to be changing from the perspective of human agents; God could sustain the universe in one changeless act if the stasis theory is true because the universe would not undergo real ontological change with time. However, it does not seem that the stasis theory of time is true.

Conclusion: God is Relatively Timeless

This article has argued that if there is a change in an effect then there must be a change in some of the causes of that effect. Given the process theory of time the universe is constantly changing. Given the truth of Christian theism, God acts to sustain a constantly changing universe. If God is the ultimate cause of changes in our universe then there must be real changes in God.

If the static theory of time is true the universe only seems to be changing from the perspective of human agents; God could sustain the universe in one changeless act if the stasis theory is true because the universe would not undergo real ontological change with time. However, we have discovered no good reason to think the stasis theory is true. God changes to sustain a changing universe. Change requires a duration, therefore God undergoes durations; therefore God is, in some sense, in time.

Bibliography

Craig, W.L. and Moreland, J.P. (2004) Philosophical Foundations of a Christian Worldview IVP Academic: Downers Grove

Helm, P. (2001) “Divine Timeless Eternity”, in Ganssle ed. God and Time: Four Views IVP Academic: Downers Grove

Helm, P. (2010) Eternal God: A Study of God Without Time Oxford University Press: Oxford

Padgett, A. (1992) God, Eternity and the Nature of Time St Martin’s Press: New York

Padgett, A. (2001) “Eternity as Relative Timelessness”, in Ganssle ed. God and Time: Four Views IVP Academic: Downers Grove

Wolterstorff, N. (2001) “Unqualified Divine Temporality” in Ganssle ed. God and Time: Four Views IVP Academic: Downers Grove

Taliaferro, C. (1998) Contemporary Philosophy of Religion Blackwell: Oxford