Personal stories and national myths are potent things.

Newly elected Irish Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, has told Time magazine that he “would like Ireland to become what Michael Collins described as the shining light unto the world.”

To many Christians the language will sound like an echo of the Sermon on the Mount and in what was once a staunchly Catholic country the Irish Times appeared to hear the resonance.

Deliberate or not, Ireland (North and South) has sufficient religious history to recognise the echo, and its source.

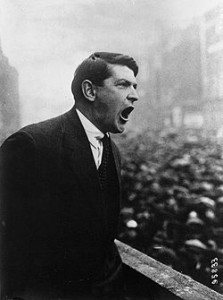

The Michael Collins quoted in Varadkar’s interview was a prominent figure in the campaign for Irish independence in the early 20th Century and a participant in the Easter Rising in 1916. During the rising the Proclamation of the Irish Republic was given its first public reading; it begins with these words:

The Michael Collins quoted in Varadkar’s interview was a prominent figure in the campaign for Irish independence in the early 20th Century and a participant in the Easter Rising in 1916. During the rising the Proclamation of the Irish Republic was given its first public reading; it begins with these words:

“In the name of God and of the dead generations from which she receives her old tradition of nationhood, Ireland, through us, summons her children to her flag and strikes for her freedom.”

Echoes, again, of religious thought, and of the old gods – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ériu. A similar thought returns towards the end of the Proclamation:

“We place the cause of the Irish Republic under the protection of the Most High God, Whose blessing we invoke upon our arms…”

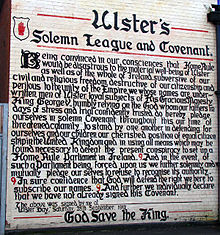

This Home Rule Crisis of which the Easter Rising was a part saw the publication of another (opposing and earlier) national and religious document: Ulster’s Solemn League and Covenant, signed by almost half a million Irishmen and women in Belfast, 1912. Like the Proclamation it, too, tends towards the religious:

“…we, whose names are underwritten, men of Ulster, loyal subjects of His Gracious Majesty King George V., humbly relying on the God whom our fathers in days of stress and trial confidently trusted, do hereby pledge ourselves in solemn Covenant…”

“In sure confidence that God will defend the right, we hereto subscribe our names.”

That such national and religiously motivated documents were possible in the early 20th Century should be of no surprise. What might be more surprising is that the echoes continue to ring over one hundred years later, and into the ‘secular’ 21st Century – but nation and tribe has always been a part of human identity, and so it remains.

That such national and religiously motivated documents were possible in the early 20th Century should be of no surprise. What might be more surprising is that the echoes continue to ring over one hundred years later, and into the ‘secular’ 21st Century – but nation and tribe has always been a part of human identity, and so it remains.

And the contemporary echoes are interesting for another reason – for this time the nation itself is the “shining light”.

Whatever we think of the torturous relationship between politics and religion, national identity and one’s identity as a citizen of the Kingdom of Heaven, the idea that the nation itself can provide the light we and others need requires a self-confidence beyond that which either the Irish Republicans of the Easter Rising or the Irish Unionists of the Ulster Covenant claimed for themselves.

But national identity and the personification of the nation is an enticing and enduring myth, and a useful story of oneself. And, like many of the stories we tell ourselves, it is intended to promote self-confidence and self-identity.

Beyond it’s more recent history, Ireland is awash with myths and identities.

Among her earliest inhabitants were the Tuatha De Danann (the People of the Goddess Dana), driven underground by the invading Milesians to become the spirits, gods and fairy-folk of the Otherworld – Tir na nOg – the Land of the Young. And they live still, by their magic arts and cloak of invisibility among the green mounds and ancient fortresses of the land. People whose fairy thorns and fairy mounds must not be disturbed.

From this perspective, Ireland is really two Irelands: the earthly and the spiritual; a land inhabited not only by mortals but also by The People of Dana – and with the intermingling of their stories and the Celtic myths, stories of nationhood were born.

All such stories are really stories about ourselves, and every people group or nation will have their own.

And lives continue to be patterned after these and other stories – local customs still respect the fairy thorn, and at the appointed time of the year we celebrate spirits of Dana as they cross from the Otherworld to ours.

And lives continue to be patterned after these and other stories – local customs still respect the fairy thorn, and at the appointed time of the year we celebrate spirits of Dana as they cross from the Otherworld to ours.

In his interview with Time magazine, Leo Varadkar went on to say,

“I would like Ireland to become what Michael Collins described as the shining light unto the world. A country that people look to for example, for example in terms of things like our economic progress, the strength of our economy, our success as a trading nation and more recently in terms of social liberalism, although we have more to do in that space.”

Here, again, is the national myth: the story by which we construct an identity – one of history, wealth, and society; one by which we give ourselves meaning and purpose, and by which we live – for man shall not live by bread alone.

But what are we to make to these personal stories and national myths which build our identities – these, and the smaller ones, the little myths and memories

We place an immense confident and trust in them, yet, at the same time we say something odd.

A popular critique of religion is concerned with our human propensity for story telling.

We like stories. And not only do we like stories, we tell stories; and the stories we tell help us to construct the hope, purpose, meaning and morality which help us to live… hopeful, purposeful, meaningful and moral lives.

And God, or the gods, just happen to be one of the chapters.

Our stories, then, be they big or small, national or personal tell us who we are – but stories are all they are.

Another more particular version of the idea is that we are hard-wired to believe in the story of a watching, judging super-natural agent who ‘cares’ about how we live and behave. This is, perhaps, the biggest of our stories and it has been told because our “social reputation” (what we might call our moral behaviour) matters to us and to the grou

Something is watching us, it seems, but whatever it is we must realise that this too is only a story and need not be true.

All that is required is that people once believed the story for its positive effects to follow and to do us good. ‘God’ is an idea that works, is a means of forming an identity and of ordering society – but that is all it is – and idea, a story.

Presented this way, the ‘god-story’ that human beings have developed and retained an esoteric or ‘spiritual’ awareness of a cosmic ‘Other’ claims to provide an answer not only for the religious behaviours so prevalent in human behaviour, but also for the pursuit of meaning and story-telling which drives and defines us, believer and non-believer alike.

But the critique presents us with a problem:

Belief in God works, but God does not exist.

I am ‘set-up’ to believe in God, but God is not there.

We need God, but he is not real.

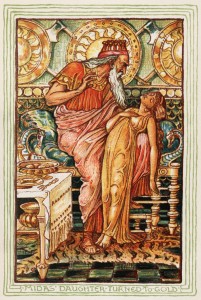

And the problem of the god story quickly becomes a problem for the national story. We perpetuate the myth of a nation personified – as Eriu, Britannia or Lady Liberty – but she cannot deliver what is promised.

Eriu is not a light unto the world.

Britannia does not rule the waves.

Liberty cannot possibly bear the hopes and needs of the world’s huddled masses.

We need the nation, but she is not real either.

At a personal level too, our own smaller, simpler story telling demands a weight of self-confidence we cannot bear. For not only must I tell my stories, I must accept that every story, every success, every chicken chasing tale is, also, infact, me.

Personal stories and national myths are potent things, but we have backed ourselves into a corner.

We are being asked to accept that human beings prosper by living as if God is there and by saying that he is not.

To accept that profitable, prosperous lives require a narrative of national proportions, one which can connect our lives one to the other, and grant us meaning and purpose.

To accept ourselves for what we are: we are meaning makers, who make only happy illusions; or, more subtly, receive our meaning as real, but only ‘real’ for me.

But in doing so we deny first ourselves and then the interconnectedness of our world. And in the end our own words fail us, for we must define what we are and at the same time forsake it.

Well, ’tis pretty make believe… , but I don’t have the faith for it. And I find that my my words collapse under the weight of their own expectations; so I look elsewhere, to a Word before which all other words must bow.

Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes from the mouth of God.

Matthew 4:4

Beyond all of that, return again to The Story of God, and ask yourself what is really being said. Surely, that without a watching eye we are all sinners. Good for goodness sake?